- Overview

- The core concept: FDA’s “4 criteria” test for Non-Device CDS

- Criterion 1: The bright line—images, signals, and “patterns” push you toward device status

- Criterion 2: “Medical information” includes patient data and trusted clinical references

- Criterion 3: CDS should “support,” not drive the clinician’s decision

- Criterion 4: Transparency isn’t optional—FDA wants clinicians to understand “why”

- CDS for patients and caregivers: generally device territory

- Examples the FDA clearly treats as “device software functions”

- A practical compliance-style checklist for Non-Device CDS positioning

- Closing thoughts: What to do next

Overview

On January 6, 2026, the FDA issued an updated final guidance, “Clinical Decision Support Software: Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff,” replacing the prior version dated September 28, 2022. This document is nonbinding, but it’s an important signal of how the FDA is drawing the line between CDS that is not a medical device (“Non-Device CDS”) and CDS that is regulated as a device.

Below is a practical, plain-English walkthrough of the guidance’s biggest takeaways—especially the parts most likely to impact product design, labeling, and regulatory strategy.

The core concept: FDA’s “4 criteria” test for Non-Device CDS

FDA anchors the guidance around Section 520(o)(1)(E) of the FD&C Act. A CDS software function is excluded from the device definition only if it meets all four criteria:

- Does not acquire/process/analyze medical images, IVD signals, or patterns/signals from signal acquisition systems

- Is intended to display, analyze, or print medical information (patient-specific or other medical info like guidelines and peer-reviewed studies)

- Is intended to support or provide recommendations to a healthcare professional (HCP) about prevention/diagnosis/treatment

- Is intended to let the HCP independently review the basis for the recommendation, so the HCP does not rely primarily on the software’s output for an individual patient decision

Think of these as the “gatekeepers” to Non-Device CDS status: fail any one, and you’re likely in device territory.

Criterion 1: The bright line—images, signals, and “patterns” push you toward device status

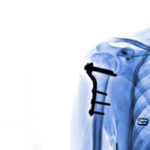

The guidance is explicit: if your CDS acquires, processes, or analyzes a medical image (CT/MRI/X-ray, pathology/derm images), an IVD signal, or a pattern/signal from a signal acquisition system, it generally does not meet Criterion 1 and remains a device if intended for a medical purpose.

“Pattern” is a keyword (and a common pitfall)

- FDA interprets pattern as multiple, sequential, or repeated measurements—for example:

- ECG waveforms/QRS complexes

- NGS sequences and VCF-type variant datasets

- CGM readings over time

By contrast, discrete, point-in-time measurements (like routine vital signs at a visit) generally don’t create a “pattern” by themselves. Practical implication: If your model ingests streaming physiologic data (or frequent sequential readings) and interprets clinical meaning, the FDA is signaling that you’re likely in device territory.

Criterion 2: “Medical information” includes patient data and trusted clinical references

FDA interprets “medical information about a patient” broadly—demographics, symptoms, certain test results, discharge summaries, and other information used in clinical care.

It also includes other medical information, such as:

- Clinical practice guidelines

- Peer-reviewed clinical studies

- Textbooks

- FDA-approved drug/device labeling

- Government recommendations

A useful nuance: device outputs (including IVD test results) can be “medical information” under Criterion 2 when used consistent with FDA-required labeling—but using continuous outputs as a pattern may trigger Criterion 1 concerns.

Criterion 3: CDS should “support,” not drive the clinician’s decision

FDA describes Non-Device CDS as software that enhances, informs, or influences an HCP’s decision-making, without replacing or directing the HCP’s judgment.

The guidance provides many examples that typically fit Criterion 3 (assuming other criteria are met), including:

- Order sets aligned to guidelines.

- Drug–drug / drug–allergy interaction alerts.

- Matching patient records to clinical guidelines.

- Lists (or prioritized lists) of treatment/diagnostic options.

A notable 2026 shift: “single recommendation” flexibility via enforcement discretion

A key update highlighted by multiple legal/regulatory analyses: FDA says it intends to exercise enforcement discretion in certain scenarios where the CDS produces a single clinically appropriate recommendation, so long as the function otherwise fits within the Non-Device CDS framework.

Why it matters: In real clinical workflows, sometimes there is one best next step. This change reduces pressure to artificially present multiple options purely to satisfy a “plural recommendations” interpretation.

Criterion 4: Transparency isn’t optional—FDA wants clinicians to understand “why”

Criterion 4 is the heart of the guidance’s transparency push. FDA’s view: to stay outside device regulation under 520(o)(1)(E), the software should be designed—and labeled—so an HCP can independently review the basis for the recommendation and not rely primarily on it.

FDA recommends that the software or labeling include (in plain language):

- Intended use and users, including the patient population

- And importantly, the FDA says that software intended for critical, time-sensitive decisions generally does not meet Criterion 4 because clinicians lack time to independently review the basis.

Inputs required, how they’re obtained, relevance, and data quality needs

Algorithm development and validation summary, including:

- General approach (e.g., meta-analysis, statistical modeling, AI/ML)

- What data was used, and whether it represents the intended population

- Results of clinical validation and known limitations

Outputs that include context, like missing/odd inputs, and patient-specific factors used in the logic

FDA also calls out automation bias—people tend to over-rely on automated suggestions, especially in urgent settings—reinforcing why time-critical tools face a steeper climb under Criterion 4. Bottom line: The more your tool is a “black box” to the clinician, the more likely the FDA is to view it as a regulated device.

CDS for patients and caregivers: generally device territory

The guidance states that CDS intended to support or provide recommendations to patients or caregivers (non-HCPs) meets the definition of a device, and the FDA points developers to existing digital health policies for how it applies oversight and enforcement discretion in that space.

Examples the FDA clearly treats as “device software functions”

FDA lists many examples that remain devices—especially where software:

- Analyzes medical images (CAD, segmentation, stroke differentiation, etc.)

- Interprets physiologic waveforms or continuous monitoring streams

- Generates time-critical alarms (e.g., stroke/sepsis alerts)

- Produces a definitive diagnosis or directs immediate intervention

If your product roadmap includes any of the above, your regulatory planning should assume device oversight and then work backward to determine classification, pathway, evidence, and quality system needs.

A practical compliance-style checklist for Non-Device CDS positioning

If your goal is to align a function with the FDA’s Non-Device CDS framing, you should be able to answer “yes” to all of the following:

- Inputs: Are you avoiding image/signal/pattern analysis (no waveform/stream interpretation, no imaging analytics, no genomic pattern interpretation)?

- Data type: Are your inputs “medical information” like discrete labs, documented findings, EHR data, and validated references?

- User: Is the intended user an HCP (not a patient/caregiver)?

- Role: Does the tool support clinician judgment rather than replace/direct it—especially in urgent scenarios?

- Explainability: Can an HCP understand the basis—inputs, logic, validation, limitations—without information overload?

Closing thoughts: What to do next

FDA’s 2026 update doesn’t rewrite the CDS rulebook—but it sharpens the boundaries, expands practical examples, and puts heavier emphasis on clinical transparency and avoiding time-critical “black box” reliance.

If you develop CDS, the best next step is to map each software function (not just the overall product) to the four criteria, document where you might fail a criterion, and decide whether to (a) redesign, (b) rely on enforcement discretion where applicable, or (c) proceed as a regulated device with an appropriate regulatory strategy.