U.S. FDA Medical Device Oversight: Overview

Distinguishing the terms “FDA-approved” and “FDA-cleared” is important. This article will review the FDA approval and clearance process for medical devices so you can understand the different terms.

The FDA regulates the sale of medical devices and monitors the safety of all regulated medical products. Before a medical device can be sold or marketed in the U.S., the FDA must approve or clear the device. The FDA clears the device for sale because it is substantially equivalent to already approved devices.

Medical Device Classes

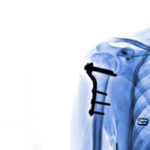

The regulatory requirements for a medical device are primarily based on the risks that the device poses based on its intended use. Medical devices are grouped into three classes, with Class I representing the lowest risk (such as tongue depressors), Class II representing moderate risk (such as surgical drills), and Class III comprising the highest risk device (such as replacement heart valves).

Each class has its own forms of regulatory oversight, with Class I requiring the least stringent and Class III the most. In addition, each class receives a different form of approval, with Class II receiving a Premarket Notification (PMN) or clearance, and Class III receiving a Premarket Approval (PMA). [1, 3, 6] The evidentiary burden in each type of review is also determined by class.

Premarket Clearance

In order to receive a PMN, the manufacturer must submit a 510(k) application, along with sufficient evidence to show that the new device is “substantially equivalent” to an already marketed device. [7] Manufacturers can prove that a device falls into the 510(k) category by demonstrating that the new device meets one of two criteria:

- The intent for use is the same as its predecessor and possesses the same or comparable technological specifications as its predecessor.

- The intent for use is the same as the predicate but features different technology without posing different or new concerns regarding its safety and efficacy.

In this manner, the manufacturer shows to the FDA that a product is as safe and effective as its predicate device and can receive “clearance” from the agency. [1, 3, 7] The PMN process is fairly quick, as the FDA will typically make its determination of substantial equivalence within 90 days of the manufacturer’s submission of the 510(k). [7]

Note that the FDA does not expect the new device be identical to the predicate. To do so would be to greatly slow down the technological progress of devices. Instead, 510(k) designations demand that the technological innovations match or exceed the fundamental safety and efficacy standards of the comparator device. [7]

The clearance can come with some conditions, however. Class II devices are subject to “special controls,” which can include performance standards, postmarket surveillance, patient registries, and special labeling requirements. [8]

Medical developers, foreign exporters, and manufacturers (including repackagers and relabelers) bear the responsibility of making sure their medical device product is cleared by the FDA before it can be introduced to the market.

Premarket Approval

In order to receive FDA approval, manufacturers of Class III devices must submit both a PMA application and the results of rigorous clinical studies that show a device is safe and effective. Class III devices include those that are intended to support or sustain human life or prevent impairment of human health or that may present unreasonable risk of illness or injury when in use. [9] Class III devices often involve novel concepts and new technologies, such as artificial organs or implantable microchips with cutting-edge software or artificial intelligence features.

A PMA is the most stringent type of medical device application required by the FDA. A PMA requires the FDA to determine that the applicant has provided sufficient scientific evidence that a device is safe and effective for its intended use. [9] The PMA application is typically very detailed and can run more than 1,000 pages in length.

The standard for evidentiary proof is that the clinical trial results must demonstrate that the benefits of a Class III device outweigh the known risks of its intended use. In light of this benefit/risk ratio determination, the FDA is more likely to approve a device carrying significant risks if its benefits are great. [10]

There are some medical devices that could arguably rest on the borderline between Class II and Class III. There is a strong incentive for manufacturers to contend that a device is Class II, rather than Class III, largely to avoid the costs and time required to run clinical trials. Fortunately, there are mechanisms by which these borderline cases can be resolved. A manufacturer can request feedback from the FDA on the classification of a medical device through either an informal Q-submission meeting or through a formal request for a device determination from the FDA. [11, 12]

Investigational Device Exemptions

A sponsor of a clinical study (most often the device manufacturer) can obtain an Investigational Device Exemption (IDE). An IDE must be approved before a device can be entered into a clinical trial and authorizes the medical device product to be shipped legally for investigation purposes without a need for complying with the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act’s regulations governing commercially marketed devices. An approved IDE allows a device to be used in a clinical trial accumulating data on safety and effectiveness. Clinical trials are most often conducted to support a PMA application, however a small percentage of 510(k) applications also require clinical data. [13]

The requirements for entering a medical device into a study that has not been first cleared or approved requires the following [2]:

- An Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved investigational plan on file.

- An approval from the FDA if the device is deemed “significant risk.”

- Informed consent must be on file from all participating subjects.

- Clear labeling stating the product is being studied is under FDA investigational status.

- Monitoring of the study.

- Accurate reporting and record keeping.

Clinical studies for Class III medical devices resemble those undertaken for the approval of new drugs or biologics. Studies submitted to support a PMA application need to be based on valid clinical information and sound scientific reasoning. [9] The process can take years to complete and involve thousands of clinical trial subjects.

Investigator Responsibility

Clinical trial investigators carry a host of responsibilities, and meeting FDA requirements for safe, ethical, and effective trials is no easy feat. Mismanaging the paper trail is one of the most common oversights. [14] Investigators work under conditions that tend to change quickly, and oversights may occur. Because human oversight can disrupt the clinical trial process, risk mitigation strategies help offset the potential for costly violations. [15] The good news is that the FDA works closely with both the sponsors and the trial investigators to maintain a streamlined approach to managing the medical device pipeline, but unexpected challenges can occur.

The regulatory pathways are extraordinarily complex, and changes occur frequently. Paired with the shift towards international and remote clinical study locations, the mandatory flow of documentation management is daunting and one of the most arduous tasks that falls under the investigator’s responsibility. Electronic record documentation facilitates the process, but it is not a flawless system, and oversights may result in an FDA warning letter and, sometimes, worse. [16] The electronic paper shuffle can create errors and oversights concerning patient consent, PMA, PMN, or IDE documentation requirements. Therefore, it behooves investigators in medical device clinical trials to develop and follow Good Documentation Practices (GDP) in their clinical research. (See CITI Program’s Biotility: Good Documentation Practices (GDP) course)

The Physicians Responsibility: Off-Label Use

Medical device products used for a clinical purpose other than the label indications recommended are considered off-label medical devices. Medical device regulations require device labels to define the indications for use and demonstrate the best applications for safety with plenty of evidence to support an approved indication. When physicians or other healthcare providers prescribe a device for a purpose other than the specified indication, that practice is considered an off-label use. [4]

The practice of off-label prescription is widespread and can have implications for clinical trials by providing real-world evidence of new indications. [17] However, off-label uses come with the possibility of unknown side effects and complications.

The practice of physicians prescribing devices off-label to gain more knowledge to determine the best indications for use is widespread. However, sponsors must still follow FDA regulations when they want to update the device’s label.

Summary

Now you should understand the difference between “cleared” and “approved.”

- For medical devices that are substantially equivalent to already approved devices, the manufacturer can submit a Premarket Notification (also called a 510(k)) to the FDA. These would be “FDA-cleared” medical devices.

- For medical devices that are new and/or different from FDA-approved devices, the manufacturer must submit a Premarket Approval (PMA) application that contains results from clinical investigations showing the device is safe and effective for its intended use. These would be “FDA-approved’ medical devices.

- For medical devices that are going to be used in a clinical investigation to support a PMA application, the manufacturer or sponsor submits an Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) to the FDA.

The space between FDA-cleared and FDA-approved medical devices is rather narrow, but it does exist. Understanding that space is the responsibility of the device manufacturer or clinical trial sponsor. Failure to recognize the proper FDA framework for medical device market candidates can result in study interruptions, application rejections, FDA warning letters, or administrative fines. Investigators should also be abreast of regulations governing clinical studies as their trials need to be FDA-compliant in order to support a new PMA.

In this light, it pays for device manufacturers to work with the FDA before filing for a 510(k) or PMA. Fortunately, the FDA is a willing and active partner in this process. In addition to providing opportunities for informal meetings and formal requests for device determinations, the FDA website provides current information regarding any regulatory changes or updates to how those changes might affect stakeholders in the medical device approval process.

References:

- Darrow, Jonathan J., Jerry Avorn, and Aaron S. Kesselheim. 2021. “FDA Regulation and Approval of Medical Devices: 1976-2020.” JAMA 326(5):420-32.

- Holbein, M.E., and Jelena Petrovic Berglund. 2012. “Understanding Food and Drug Administration Regulatory Requirements for an Investigational Device Exemption for Sponsor-Investigators. Journal of Investigative Medicine 60(7):987-94.

- Lauer, Madelyn, Jordan P. Barker, Mitchell Solano, and Jonathan Dubin. 2017. “FDA Device Regulation.” Missouri Medicine 114(4):283-8.

- David, Yadin, and William A. Hyman. 2007. “Issues Associated with Off Label Use of Medical Devices.” 2007 29th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society 3556-8.

- S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 2020. “Overview of Device Regulation.” Accessed April 25, 2023.

- S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 2020. “Classify Your Medical Device.” Accessed April 25, 2023.

- S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 2022. “Premarket Notification 510(k).” Accessed April 25, 2023.

- S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 2018. “Regulatory Controls.” Accessed April 25, 2023.

- S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 2019. “Premarket Approval (PMA).” Accessed April 25, 2023.

- S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 2019. “Factors to Consider When Making Benefit-Risk Determinations in Medical Device Premarket Approval and De Novo Classifications.” Accessed April 25, 2023.

- S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 2021. “Requests for Feedback and Meetings for Medical Device Submissions: The Q-Submission Program.” Accessed April 25, 2023.

- S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 2019. “FDA and Industry Procedures for Section 513(g) Requests for Information under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.” Accessed April 25, 2023.

- S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 2022. “Investigational Device Exemption (IDE).” Accessed April 25, 2023.

- Heering, Clara. 2016. “What Errors Do We Miss in Clinical Trials?” Pharmaceutical Executive 36(3). Accessed April 25, 2023.

- Hastings, Rebecca, and Holger Liebig. 2009. “Reducing Risk Through Mitigation Strategies.” Applied Clinical Trials 0(0). Accessed April 25, 2023.

- Nichols, Etienne. 2023. “FDA Form 483 Observations and Warning Letters – What’s the Difference?” Greenlight Guru Blog, February 1. Accessed April 25, 2023.

- S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 2017. “Use of Real-World Evidence to Support Regulatory Decision-Making for Medical Devices.” Accessed April 25, 2023.