Season 1 – Episode 41 – Unpacking the FDA’s Revised CDS and General Wellness Product Guidances

Discusses key takeaways from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s revised Clinical Decision Support Software and General Wellness Product guidance documents.

Podcast Chapters

Click to expand/collapse

To easily navigate through our podcast, simply click on the ☰ icon on the player. This will take you straight to the chapter timestamps, allowing you to jump to specific segments and enjoy the parts you’re most interested in.

- Introduction and Guest Background (00:00:03) Host introduces the podcast, guests, and their expertise in FDA regulatory practice for digital health and emerging technologies.

- Purpose and History of FDA Guidance Documents (00:03:04) Explains the purpose of CDS and general wellness guidance, reasons for recent revisions, and historical context.

- Stakeholder and Political Context for Revisions (00:04:43) Discusses stakeholder feedback, political motivations, and timing of the revised guidances.

- Defining Clinical Decision Support (CDS) Software (00:06:16) Defines CDS software, provides examples, and distinguishes between regulated and non-regulated CDS.

- Criteria for Non-Device CDS Software (00:08:02) Outlines the four statutory criteria for CDS software to avoid medical device regulation.

- Key Takeaways from Revised CDS Guidance (00:10:38) Highlights main changes in the revised CDS guidance, especially regarding recommendations and risk scores.

- Impact of Single Recommendation Policy (00:14:07) Explains why the single recommendation issue was problematic and what the new guidance enables for developers.

- Durability and Open Questions on Enforcement Discretion (00:17:54) Discusses the fragility of enforcement discretion and unresolved questions for companies.

- FDA’s View on Clinical Documentation Tools (00:20:15) Analyzes FDA’s example on clinical documentation tools and what remains unclear for developers.

- General Wellness Products: Definition and Examples (00:23:09) Defines general wellness products, gives examples, and describes the evolution of the space.

- Key Takeaways from Revised General Wellness Guidance (00:25:34) Summarizes major changes, especially regarding sensor-based wearables and physiological parameters.

- Significance of Shift on Physiological Parameters (00:29:15) Explores the importance of FDA’s new stance on physiological parameters for wellness products.

- Guardrails for Avoiding Device Regulation (00:31:02) Lists critical boundaries companies must observe to keep wellness products from being regulated as devices.

- Operational Challenges in Implementing Guidance (00:32:14) Highlights practical difficulties in validating and communicating product features under the new guidance.

- AI and the Revised Guidances (00:35:45) Examines what the guidances do and do not say about AI-enabled CDS and wellness tools.

- FDA’s Broader Direction on Digital Health (00:38:10) Considers what the guidances signal about FDA’s overall approach to digital health regulation.

- Additional Resources and Final Thoughts (00:40:11) Recommends further reading, Covington resources, and emphasizes the evolving regulatory landscape.

- Closing Remarks (00:44:00) Host wraps up the episode, promotes related resources, and thanks the production team.

Episode Transcript

Click to expand/collapse

Daniel Smith: Welcome to On Tech Ethics with CITI Program. Today, I’m going to speak to Christina Kuhn and Olivia Dworkin from the law firm, Covington. We are going to discuss some key takeaways from the US Food and Drug Administration’s revised clinical decision support software and general wellness product guidance documents. Before we get started, I want to quickly note that this podcast is for educational purposes only. It is not designed to provide legal advice or legal guidance. You should consult with your organization’s attorneys if you have questions or concerns about the relevant laws, regulations, and guidance that may be discussed in this podcast. In addition, the views expressed in this podcast are solely those of our guests. And on that note, welcome to the podcast, Christina and Olivia.

Christina Kuhn: Thank you.

Olivia Dworkin: Thank you for having us.

Daniel Smith: So I very briefly introduced that you both work at Covington. What can you tell us more about yourselves and your work at Covington and what you focus on?

Christina Kuhn: Of course. So Covington is a global law firm. Both Olivia and I are in the FDA regulatory practice at the firm. It’s a very large group of lawyers who work on a variety of FDA regulatory issues. I’ve been at the firm now for about 15 years, working on the FDA at the intersection of digital health, software and emerging technologies, including AI enabled products. We advise a whole range of companies, including the more traditional hardware medical device companies, emerging companies and startups, and then health tech companies and general tech companies that are thinking more about health these days, primarily on whether and how their products will be regulated by FDA as medical devices. If they are going to be regulated, how they can comply with the FDA regulatory framework, getting to market and staying compliant once they’re on market. And if they’re going to try to avoid being FDA regulated, what are the guardrails for doing that so they don’t end up in an enforcement situation. Olivia?

Olivia Dworkin: I’m a senior associate in our Los Angeles office. I’m also in our food, drug, and device practice group at Covington, and I work very closely with Christina and others in our group on the matters that she just mentioned. But I also wanted to note that probably relevant to our conversation today, a big part of our practice is really translating FDA policy that’s often expressed in guidance documents like the ones that we’ll discuss today. And to really practical advice for product teams to help them think strategically about how to design and position products in what everyone I’m sure will know is a fast moving regulatory environment. We also work with companies to provide comments and feedback to Congress and other regulatory agencies on these evolving frameworks to help shape the landscape moving forward. And our FDA team is just one piece of our broader global digital health initiative at Covington. So we also work closely with colleagues in other sectors and other jurisdictions to cover issues like privacy, product liability, and where global regulators are aligned and maybe taking different approaches on these issues.

Daniel Smith: That’s wonderful. It’s great to have you both again. So as we’ve alluded to, FDA kicked off 2026 by releasing revised guidances on clinical decision support software and general wellness products. But for someone new to FDA digital health regulation, what is the purpose of these two guidance documents and why did FDA recently revise them?

Christina Kuhn: So to back up to the bigger picture you’re raising, FDA has been thinking about for almost a decade, how to articulate those products the agency wants to regulate and those that doesn’t in the sort of software and wellness spaces. One of these guidances goes back almost a decade that hasn’t changed that much. And FDA’s had other guidances where they’ve in the digital health space articulated again what’s going to be regulated or not. And at the end of 2016, Congress actually codified part of that, part of the 21st Century Cures Act where they put in the law certain types of software that is exempt from medical device regulation. And one of those what we call clinical decision support that was a new category at the time that FDA has interpreted it by guidance. That law also said that general wellness software is not a device.

Given the Trump’s sort of emphasis on deregulation and promoting innovation, advancing AI, the agency’s policies on wellness and decision support and digital health more broadly were an area where I think many folks expected revision because it seemed like an easy area where the administration could sort of loosen the rein, so to speak, and allow more AI and other types of products to enter the market without FDA regulation.

Olivia Dworkin: Yeah. I’ll just add on CDS in particular, when we’re thinking about why these guidance documents and why now. I wanted to mention that the final guidance that FDA issued on CDS in 2022 was an area where a lot of notable stakeholders, including Republican Congress members like Senator Bill Cassidy, viewed FDA’s prior interpretations as perhaps overly restrictive and maybe stifling innovation. So we’ve been anticipating some changes to that guidance for quite some time now to address some of that criticism and that feedback that the agency was getting. And then on wellness, I’ll say the changes to the guidance really align with broader attention to consumer wearables that we’re seeing at the federal level. We know that HHS Secretary RFK Jr. has a big campaign to encourage the use of sensor-based wearables. And then just the timing of these announcements to Marty Makary, the FDA commissioner, announced these guidances at the consumer electronic show, which is a really high profile tech conference. So to Christina’s point about the pro AI, pro innovation stance that this administration is taking, the timing of these announcements was also pretty notable.

Daniel Smith: Certainly. So I want to dive into both guidances in a bit more detail. So I’m going to start with the revised clinical decision support software guidance. So Olivia, another question for you just as level setting for our audience is what is clinical decision support software? And can you also provide some examples of different products that would be considered CDS?

Olivia Dworkin: Sure. So as a category, clinical decision support software or CDS is really software that helps clinicians make decisions about the diagnosis or treatment of their patients. Typically, that software will analyze patient specific information and offer recommendations to clinicians. Within that category, some CDS tools are medical devices that are regulated by FDA and some are not. Some are excluded from the definition of a medical device. And I’ll provide a few examples, software that access a first or second reader of radiology images. So if it’s analyzing a radiology image to identify a region of interest or to make measurements to help a radiologist in their interpretation of the image, that’s something that FDA has regulated as a medical device. But then on the non-device CDS side of the line, we also have software that does things like matches patient specific information to reference information like clinical guidelines and provides contextually relevant reference information about diseases or conditions or recommendations for clinicians to consider and sort of support their evaluation of a patient.

And I also wanted to note that when we talk about CDS, we’re typically talking about decision support for licensed healthcare professionals, but you may also hear terms like patient facing or caregiver facing decision support, which is not covered by this CDS guidance but has been spoken about by FDA in the past.

Daniel Smith: So you mentioned CDS that is regulated as a medical device and then non-regulated CVS. So at a high level, can you just go over the criteria that must be met for clinical decision support software to avoid regulation as a medical device?

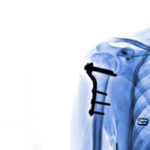

Christina Kuhn: There are four criteria in the statute, and if the decision support meets all four of them, then they’re not a medical device. The first two criteria go hand in hand as they both relate to the types of inputs that the software can analyze. So in order to remain out of device regulation, the software cannot analyze a medical image. So like a CT, an MRI, or even a photo someone takes on their phone of a skin condition, it cannot analyze the underlying physiological signals that are typically measured by a diagnostic or a medical device. So things like EKG weak waveforms or the fluorescence in a specimen, and it cannot analyze patterns or sort of repeated sequential measurements. So again, EKG waveform, sort of continuous glucose monitoring where you have this continuous pattern. If you analyze any of those, then you’re out of the criteria and you’re likely going to be regulated as a device.

What you should be analyzing or what FDA calls medical information, sort of discrete, largely text-based information about the patient symptoms, medical history, the results of lab tests or the results of a radiology report, sort of what someone evaluated from those medical images, the kinds of information we know a doctor might review in a chart, for example, is what you can analyze. The third criterion, so those were the first two. The third goes to what is the output? What can you tell to the user? And there’s two parts to this. It must be recommendations and they must go to a healthcare professional to Olivia’s earlier point. To the healthcare professional part is clear. We’re not talking about anything that goes to patients or other caregivers. Recommendations is the part where we’ve seen a lot of action where we’ll see the revisions in this guidance, what is the recommendation and what is not.

And then the fourth criterion goes to this human in the loop concept and transparency and says that to avoid regulation, the software needs to enable the healthcare professional to independently review the basis for the recommendation. So they’re relying on their clinical judgment informed by the software output, but not relying exclusively on that software.

Daniel Smith: That’s really helpful. And I think that gives us a good base understanding of clinical decision support software. So I know the revised guidance sheds some light on the FDA’s thinking around the previous guidance. So can you walk through some of the key takeaways from the revised guidance?

Christina Kuhn: The main revision relates to that third criteria and that concept of providing recommendations. In the prior guidance which was issued in 2022, FDA had defined this pretty narrowly and said that software only meets these criteria and it provides recommendations only when it provides a list of options. So software that provides any sort of singular output would not be exact and would be regulated. So that included things like a specific treatment course or a treatment plan. It provides a specific recommended diagnosis or things that provide a risk score. All of those things were not exact. And as Olivia said, folks thought that went a little bit too far. That’s a lot to read into the plural form of recommendations being in the statute. And FDA is now relaxing that a little bit. What they’re saying is you can provide sort of a single option in lieu of a list when only one option is clinically appropriate.

So if you’re recommending treatment plans, you should be providing options, but if there’s really only one treatment that’s clinically appropriate, you can provide one. And FDA also says a little bit more leeway on things like risk scores where if it’s like a one-year risk score for re-hospitalization after procedure, that can also be a clinically appropriate singular recommendation. So those are all these new examples, things that would have been regulated under the prior guidance, but now FDA is giving some more leeway to do and still avoid medical device regulation.

Olivia Dworkin: And just adding onto that, one takeaway that I was really interested to see, and this may be flying more under the radar, is just one example that FDA added that discussed clinical documentation tools. This is an area where we’ve seen global health regulators coming out and taking different approaches to whether those types of ambient scribing tools, clinical documentation tools are regulated as medical devices and which are and which are not. So I, for one, have been waiting to hear FDA’s thoughts. This is an area where we haven’t heard a lot from the agency on how they’re viewing these types of tools. FDA added an example in the new guidance suggesting that software that generates a proposed summary of a radiologist’s clinical findings and diagnostic recommendations for a patient report, even if it includes just one diagnostic recommendation, is subject to enforcement discretion under that framework that Christina was just describing, meaning the FDA does not intend to enforce device requirements. At least for that one bucket of clinical documentation tools.

So I was excited to see at least a limited window into FDA’s thinking for that category. And then FDA also made some other relatively surgical edits, I’ll say, to some other things that popped up in the prior guidance, like whether software can aid in time critical decision making that was previously type of software that was discussed under criterion three about whether that a time critical recommendation could be a recommendation or whether that failed that criterion. Now that discussion has just been moved to criterion four. So now FDA is analyzing whether if information is surfaced in a time critical scenario, can a healthcare provider really have time to independently review the basis for the recommendations and come to their own decision?

Daniel Smith: So Christina, you mentioned that’s probably the biggest changes around the single recommendation. So why was FDA’s treatment of single recommendations such a pain point under the prior guidance, and what does this revised guidance practically unlock for developers?

Christina Kuhn: So under the previous guidance, I think one, the concept that it had to be a list of options was practically hard to implement because there are a number of clinical scenarios where a list may not be clinically appropriate. And FDA’s guidance included examples of software that met the criteria, but presumably would at least in some cases provide only a single option. For example, FDA had said drug-drug interaction software that provides an alert if you’re prescribing a drug that has a known interaction with another drug the patient has been prescribed, that could be exempt clinical decision support that could meet the criteria, but presumably that kind of software only provides a single output, either there’s an alert or there’s no alert. And FDA talks a lot about matching patient information to approve drug labeling or to clinical practice guidelines. But if you do that, there may only be one option.

There’s only one recommended dose under the drug labeling, or only one recommended treatment. So that left people in this bind of, does my software have to make up options that I can have multiple options? Is it okay if the software’s designed to surface multiple options most of the time, but sometimes doesn’t? What does that mean? And as Olivia said, there was this view of like, why are we even talking about this list of options? Why can’t a single piece of information be a recommendation? Doctors can understand that as a suggestion to use in their decision making. They don’t necessarily need a list to say, “Oh, I need to understand that this might still not be right for my patient.” So this change now clarifies that and says, all of those examples I was talking about, yes, where it’s clinically appropriate, you can have a singular output.

You don’t have to make up options or avoid talking about those scenarios to fall within the exemption, which is a very helpful clarification. I think it helps folks feel more comfortable who are already interpreting the guidance that way because practically that’s what made sense. The piece of it that I think is actually a bigger shift is this concept of risk scores because FDA was pretty clear before that any risk probability or risk score was a no-go if you wanted to meet the criteria and avoid regulation. And now FDA is saying is you can provide certain types of risk scores and the agency won’t regulate you as a matter of their enforcement discretion. So they give an example of a 90-day or one-year risk score of hospitalization for a patient post-transplant as being unregulated, but software that predicts the risk of intraoperative or hospital mortality based on near time measurements to guide an immediate escalation, that risk score would still be regulated, would still fail the criteria.

So that opens up quite a lot of room actually because there was a lot of softwares at least that we were working with that wanted to do some degree of risk score. There’s a lot of risk categorizations out in the literature that maybe required a complicated calculation that would be great if it could be automated, or folks are crunching their own data to come up with risk scores and risk stratification. So that opens the door. We still have the question of like, between immediate and 90 days, how much leeway do we have? But I think it opened the door for quite a bit that wasn’t permitted before.

Daniel Smith: So since the flexibility comes through enforcement discretion rather than a change in FDA statutory interpretation, how should companies think about the durability of that approach, and what questions are left unanswered?

Olivia Dworkin: So enforcement discretion is by definition subject to FDA’s discretion. And we’ve seen examples in prior draft iterations of the CDS guidance where FDA has said that certain software is subject to enforcement discretion, most notably a software that’s intended for patients and caregivers. So patient decision support software and caregiver decision support software. Then when FDA finalized the CDS guidance in 2022, that full discussion of enforcement discretion for patient and caregiver facing software was removed. So we’ve seen examples where something that was subject to enforcement discretion may no longer be subject to enforcement discretion and future iterations of guidance. This potentially means that these interpretations are maybe fragile across different administrations and we have different people at FDA, different commissioners that are thinking about these issues differently. In this case, at least for the singular recommendations point, this was an area that did get a lot of criticism.

The enforcement discretion approach arguably is permitted under a reasonable interpretation of the statutory language. So I’m not sure that we’ll see a lot of pushback on this new category of enforcement discretion, but anything is possible.

Christina Kuhn: And just on the topic of things that are going to be hard to implement on a go forward basis, the last thing I would add is on that concept of you can have a single output when it’s clinically appropriate, that now creates this judgment call that folks will have to make on what constitutes being clinically appropriate. That might be an easy call if you’re doing things like matching something to FDA approved drug labeling or guidelines, but increasingly the interesting innovation and clinical decision support is where people are coming up with algorithms from real world evidence data sets and the like. And it’s not clear what level of validation you would need to be sure that only that single option is clinically appropriate. So that will just be an implementation question going forward, whether they’ve met that threshold.

Daniel Smith: And then one more question on the CVS guidance before we move into the general wellness guidance is, Olivia, you mentioned that clinical documentation tools have been a focus for developers in recent years and that the revised CDS guidance includes an example touching on these tools. So what does that example tell us about FDA’s current thinking and what does it leave unresolved?

Olivia Dworkin: The example that FDA included in the guidance is really helpful. It does provide sort of limited insights into how FDA is thinking about these tools, but I do want to caution that the example that they included is relatively narrow. There’s only one example that relates to clinical documentation tools, and it does have a few prongs to it. So the diagnostic recommendation that the clinical documentation tool produces should be based on clinical guidelines. It can’t use information that is not from well understood and accepted sources. The software also can’t analyze the underlying image, so it would only be able to review and analyze the radiologist’s reported findings from the radiologist review of the image, and an HCP still needs to be in the loop to review, revise, and finalize the patient report. And then all of the other non-device CDS criteria that we’ve been talking about must be met as well.

There aren’t a variety of clinical documentation tools on the market that have different features. Maybe they are producing a list of diagnostic recommendations, so they wouldn’t be captured by that singular recommendation. And for those tools, we’re left wondering whether those are all clinical decision support that meet all of the criteria. There’s also tools that don’t produce anything outside of the sort of four corners of the patient visit transcript or outside of the radiologist documented findings. So it’s not clear whether those types of tools would be viewed as supporting a clinical decision or whether those could be more administrative support tools that wouldn’t need to meet any non-device CDS criteria and would just not be regulated as medical devices. So whereas other jurisdictions, we’ve seen them have more sophisticated and developed frameworks around these clinical documentation tools. We really only have this one example from FDA. So it does show some openness to innovation in this space, but I guess this leaves developers guessing where the outer boundaries really are.

Alexa McClellan: I hope you’re enjoying this episode of On Tech Ethics. If you’re interested in hearing conversations about the research industry, join me, Alexa McClellan, for CITI’s other podcast called On Research with CITI Program. You can subscribe wherever you listen to podcasts. Now back to the episode.

Daniel Smith: Now moving into the general wellness guidance, similar to with the CVS guidance, just as kind of level setting for our audience, can you describe what a general wellness product is and some examples?

Olivia Dworkin: Sure. So as maybe a parent from the name, these products are intended for maintaining or encouraging a healthy lifestyle. And generally are unrelated to diagnosis or treatment of diseases or medical conditions. So a few examples, everyone’s probably seen those wearable products that people are wearing at the gym to track health metrics, things like watches or rings. We’ve also seen software only wellness apps such as diet apps that recommend meal plans, apps that are guiding meditation, and really just encouraging a state of overall wellness through these healthy lifestyle choices related to things like sleep, diet, exercise. There’s also some products on the market that are mixed and have both wellness and medical device features. So for example, products can track health metrics for wellness uses and purposes, but also have a function that analyzes information for clinical purpose, such as maybe to detect irregularities or abnormalities in your heart rates or heart rhythms.

So detecting things like AFib or sleep apnea with your breathing patterns while you’re sleeping. I do want to say the space has really evolved over the past decade or so. I think that the first general wellness guidance was 10 years ago, close to that. And since then, the scope of information that consumers really want access to has expanded. I think when the first general wellness guidance came out, the main parameter that was on everyone’s mind that we thought of wellness was the heart rate sensors and treadmills. And over time, more and more physiologic parameters that were traditionally only measured in clinical settings at your yearly physical were viewed as having these wellness uses. And consumers wanted to know these parameters just for information to have in their daily lives and to impact their lifestyle decisions. And they weren’t just vital signs that people wanted measured once a year. So the types of information that consumers wanted access to, and then the technology that was able to capture this information and track and trend it for users has really evolved over time.

Daniel Smith: Certainly. And I would imagine that with that evolution from the guidance that was originally released over a decade ago, that there are some significant changes here. So can you talk through some of the key takeaways from the revised guidance on general wellness products?

Christina Kuhn: So all the action in the new guidance is on these wearables that Olivia was mentioning. I think it’s really one of the first big changes we’ve seen in the wellness guidance in those 10 years. It hasn’t changed much until now. It was an area, these sensor based technologies that guidance didn’t directly address before. People just sort of interpreted the concept that as long as it’s for a wellness use for healthy lifestyle choices, you could have these sensor-based technologies. As Olivia mentioned, the heart rate sensors in the treadmills and the bikes go back a long way and no one ever tried to regulate those as medical devices. But as the evolution that Olivia was talking about was happening, there’s the innovation in what we can measure with sensibles and wearables, and the sort of consumerization of those kinds of parameters. There were increasingly questions about what was wellness or not wellness, could anything be wellness even if it has other clinical purposes, are things inherently clinical?

And it started to coming to a head in the last year or so with things like continuous glucose meters where you saw some on the market as wellness and then FDA actually cleared as devices, some continuous glucose monitors or CGMs that had a wellness intended use. So that opened the question of why were these being regulated as devices if they have a wellness intended use, and FDA never directly clarified that. And then last summer, FDA issued a warning letter to a company that was marketing a blood pressure indicator as a wellness product. And FDA said in that warning letter, the agency’s position was that if you’re displaying blood pressure values, those are inherently clinical because that’s how you diagnose hypertension. So there is no wellness version of blood pressure. The company that got that warning letter pushed back pretty strongly and said, “We disagree. We think this is wellness. We’re not changing our product.” So that created more questions and confusions about where all this landed.

So what we got in the revised guidance is that FDA has now clearly said sensor-based technologies that measure a physiological parameter like blood pressure or glucose or heart rate or blood oxygen saturation can be a wellness product. So they’re not a medical device if they have a wellness intended use and if they’re not invasive. So that seems to open up the concept that really no parameter is inherently off the table for wellness. The fact that it has a clinical purpose doesn’t preclude it from being wellness. You do need to have a wellness purpose. You can’t just have something that tells you whether you have hypertension and call it wellness. It needs to have connected to some wellness use. So exercise, have normal healthy sleep habits, diet, nutrition, stress, things that are not disease related.

If you have that, and if you’re non-invasive, which FDA has a pretty low threshold, for example, they clarified that the CGMs that they cleared as devices were considered devices because they have a microneedle that pierces a little bit into the skin and that they considered that invasive. So minimally invasive is not invasive enough to be wellness. To be wellness product, you have to be fully non-invasive essentially and have to have a wellness purpose. But if you can do that, then it opens the door for sort of any wearable sensor-based physiological parameter that could be measured.

Daniel Smith: So in terms of that shift away from physiological parameters as automatically disqualifying for wellness products, how significant is that shift and what does it signal to you about how FDA is thinking about the wellness space more broadly?

Christina Kuhn: The principle that you can have these wearables and be wellness, like I said, is not new. We’ve known that for things like heart rate for a long time, but for things like blood pressure where I read the guidance is basically FDA fully retracting its position in that warning letter. It’s pretty significant. We pretty rarely see FDA issue a warning letter saying, “This is a regulated device.” And then less than six months later issuing guidance thing, not a regulated device, which is fundamentally what happened here. So that I think is a pretty strong top down message that they want these things to be available for wellness, and that they’re going to take a broad view of what can be wellness going forward. So it leaves open the door for really any non-invasive sensor technologies now going forward to be wellness. I think there was a lot of questions, things that the guidance still doesn’t address directly like temperature.

Is that inherently a fever or can that be used if it’s one of several metrics and things like stress or sleep patterns? That’s still a little bit open, but I think the concept that really, as long as you have a justifiable wellness use and you’re non-invasive, is going to open the door for a lot more innovation.

Daniel Smith: And Olivia, you mentioned how some of these wellness products may also have device components. So can you talk a bit about the most important guardrails companies need to understand to avoid drifting into device regulation?

Olivia Dworkin: Sure. So while the revisions do open the door for a lot more general wellness products, at the same time, FDA is very clear about certain guardrails that companies need to follow if they want to stay on that wellness side of the line without drifting into a clinical purpose or medical device use for their product. So the products can’t reference diseases, you can’t generate clinical diagnoses or treatment recommendations based on the data you’re gathering. The products cannot provide ongoing alerts that are intended for disease management. The USO can’t claim in marketing materials that your product is a substitute for a regulated medical device that has received clearance or approval from FDA. As Christina mentioned, FDA has also taken a pretty broad view of what products are invasive. So even minimally invasive products like sensors with microneedle technology do not fall within this non-device general wellness category. And then products also cannot output values that mimic those used clinically.

That’s the language used in the guidance unless those values are validated. While the door is open for more products, there are still several guardrails that companies need to face when they’re thinking about the design of their products.

Daniel Smith: And Christina, I’m also wondering, are there aspects of the guidance that sound straightforward on paper, but maybe difficult to operationalize?

Christina Kuhn: I think so, yes. One of those is that last point Olivia just mentioned. While the guidance does allow you to display the actual values, and even if they’re values that are traditionally used clinically, you can only do so if you’re validated. But FDA does not describe at all what it means to be validated for that. Is that the same level of validation of clinical validation or is there some other wellness level of validation that is needed? Do you need to describe or label how those values have been validated? If so, how do you do that? Because another one of the guardrails FDA says, as Olivia mentions, you can’t claim clinical level accuracy or claim equivalence to a clinical medical device product. Presumably though, if you’re doing a validation study on the accuracy of your sensor for a particular parameter, you might pick the clinical product to be the gold standard reference product for accuracy.

So if you do that comparative study to validate your parameter to meet this requirement that it has to be validated before you can display them, then how do you talk about the fact that you validated it if you can’t say we’re compared to a clinical product? So those questions I think are going to be challenging to implement even though it does quite open the door quite a bit. The other area that might be challenging, which we haven’t mentioned yet, is the other thing FDA opens the door for in the guidance is that these kinds of wellness products may include a notification to a user that evaluation by a doctor may be helpful when outputs fall outside ranges appropriate for general wellness use. So that I think is meant to address a concern that some people have had or some developers have had where you’re measuring all this stuff about a patient and then you can see or the data can tell you that something is going a little bit haywire at that person, but you don’t tell them that there’s sort of a safety risk there.

So this opens that door. But at the same time, FDA says any such notification can’t name a disease or condition. It can’t characterize the output as abnormal, pathological or diagnostic. You can’t have clinical thresholds and you can’t have ongoing alerts. So it’s not clear what the actual alert or popup would say. You should say, evaluation by a doctor may be helpful because these outputs are outside the range of wellness. But you can’t say they’re abnormal, you can’t say they’ve expedited a clinical threshold. I’m not sure how useful that concept will be to users. It’s also not clear how you actually establish internally what is the range that’s appropriate for wellness. If that’s not in relation to certain clinical thresholds, is it relation to the user’s own baseline? And again, then what level of departure from their normal would you flag this for? So it’s a new concept that you can say you might want to see a doctor which you typically wouldn’t consider appropriate for wellness, but it’s really unclear how you would actually do something that was meaningful on an actual consumer level there.

Daniel Smith: So I want to ask about some additional resources where people might be able to learn more and think through some of these issues in more detail. But before I get to that, take a broader view of these two guidance documents together. I know you mentioned at the start of this conversation that both of these guidance documents come at a time where AI is advancing rapidly and being integrated into more products and so on. So I think many people expected these revisions to address AI. So what do these guidances say or not say about AI-enabled clinical decision support software and wellness tools?

Olivia Dworkin: So as much as we’ve heard this administration be very pro AI, pro innovation, and in Dr. McCarry’s announcement of these guidance documents, they were really advertised as relevant to AI and really opening the door, cutting the red tape, promoting innovation for AI tools. Neither guidance really squarely addresses AI or engages with AI in a really substantive way. There wasn’t discussion about many of the novel technologies that are surfacing today, such as clinician and consumer facing health chatbots. I also didn’t see discussion about AI tools and the general wellness guidance that maybe leverage data from health wearables and interact with users based on that data. For clinical decision support, there also seemed to be an emphasis in the revisions on the use of well understood and accepted sources, which was defined to include things like clinical guidelines, other peer reviewed literature and well-established sources to inform recommendations that software is giving to clinicians.

And for more traditional rules-based software that seems relatively straightforward, but when we’re talking about more advanced AI systems that are designed to surface insights from maybe complex patterns or emerging evidence that’s not published yet in peer reviewed literature or clinical guidelines, the fit is a little less clear. So we don’t get that substantive engagements with AI tools that don’t fit neatly into these four criteria to be non-device CDS, and how AI tools can satisfy those criteria. So I would say, that both guidances are more so clarification of existing policies rather than opening the doors or establishing brand new frameworks for AI.

Daniel Smith: That’s interesting. And then if you look at the two guidance documents together, what do they tell us about the FDA’s broader direction on digital health?

Christina Kuhn: To that extent it remains to be seen. So I think as Olivia just said, it was definitely a step forward in promoting innovation and trying to be a bit more flexible, but maybe not as far as we might have expected given the sort of broader political priorities. And where stakeholders thought there was room to go and still have a reasonable regulatory framework. I think it’s also perhaps showing us how the dynamics might be playing out in terms of stakeholder pressures, political priorities, and the sort of line level FDA folks who thought they were already in a good place on some of these policies. I think things like that warning letter and then retraction, presumably that specific example was both a result of, as Olivia mentioned earlier, the broader push for wearables, but also presumably some level of lobbying or political pressure on that particular example. There was a lot of public discussion about whether FDA got it right or wrong in that warning letter, and that similarly with the CDS guidance.

So maybe what we’re seeing in these guidances is that compromise between the political level wanting to do more and the line level FDA who is actually writing these guidances and signing off on these guidances feeling like they don’t want to go too far. They’re worried about opening too many things out in the market without FDA oversight, particularly as things advance. And I think what’ll be interesting to see is how FDA deals with the intersection of all these technologies. As I think Olivia alluded to, we’re going to have chatbots and things like generative AI that can connect to all these wearables, and how are they going to crunch all that data. Are they going to layer things on it? Are people going to be sharing the wearable data with their doctors? Should they, should they not? What doctors do with it? All of those pieces I think are just going to get more complicated that’ll be interesting to see how FDA handles them.

Daniel Smith: Absolutely. So you both have unpacked both of these guidance documents in a very helpful, understandable way, but for our listeners who want to learn more about them, what additional resources do you recommend?

Olivia Dworkin: So we’ve talked about some of our top level takeaways today, but we did Covington issue two more detailed client alerts on these two guidances that summarize these takeaways and a few others in more detail. So I’d encourage everyone to look at our website and take a look at those if you’re interested in learning more. We also have a digital health blog at Covington so everyone can subscribe. We do have a global cross-disciplinary digital health team that’s always monitoring these developments and reporting on that blog. So that’s a good resource to have. And then finally, I would just say to watch FDA closely, this is an evolving space. So I don’t think that this will be the last that we hear from the agency on these issues. So keeping an eye on the news will be important.

Daniel Smith: Certainly. And I will include links in our show notes to those resources that you just mentioned so our listeners can check them out. And on that note, my final question for both of you is just, do you have any final thoughts that we have not covered in today’s conversation?

Olivia Dworkin: I would say, my last point about watching FDA closely and perhaps the lack of substantive AI discussion in these two guidances, it does make me wonder whether AI specific guidance is forthcoming. The agency did host two meetings of its digital health advisory committee on gen AI enabled devices specifically, one, just generally on total product lifecycle considerations, and then another on mental health, gen AI enabled mental health medical devices. So far, we haven’t seen guidance incorporating recommendations or information from those meetings. So I’ve been watching the space to see if we get any more information from FDA on AI specifically.

Christina Kuhn: And I would just add that I think the pace of innovation in all these areas is just going to keep accelerating, and it’s going to become kind of increasingly challenging for FDA to keep up. In terms of its formal policies, I think the examples we saw today were already examples where FDA is kind of trying to catch up with what industry has already decided is appropriate and is moving forward with, and the agency is stepping in to either agree or disagree with that. And I think we’re going to see more of that challenge for everybody really of having policy keep up with where the industry is going presents an opportunity for industry to engage. Because I think FDA is looking more to understand where are these technologies going, what are the consumer needs, what’s going to be available in terms of technological advancements, and where should the policies go?

Maybe more so than there would’ve been five or 10 years ago. So I think if you’re in this space and developing, thinking about whether and how to engage FDA is something that you might think about more proactively than you did before. And then the last piece is the interplay between state and federal regulation. And we’re seeing states increasingly step in and try to regulate health related AI, particularly that’s not a medical device. So as we try to push things out of FDA medical device regulation, whether the states step in to handle that, whether state level gets preempted by the federal rules, which the Trump administration is currently pushing to preempt all these state AI laws, but then there’s pressure to do something else at the federal level so there’s not complete unregulated products out there, think as a space to watch too. So even if you’re like, “We won the battle on the FDA device regulation,” I think, especially if you’re an AI product, stay tuned on where all this is playing out.

Daniel Smith: Absolutely. Lots to look out for. I think that is a wonderful place to leave our conversation for today. So thank you again, Christina and Olivia.

Olivia Dworkin: Thank you for having us.

Daniel Smith: If you enjoyed today’s conversation, I encourage you to check out CITI Program’s other podcasts, courses, and webinars. As technology evolves, so does the need for professionals who understand the ethical responsibilities of its development and use. CITI Program offers ethics-focused self-paced courses on telehealth, digital health, AI, cybersecurity, and more. These courses will help you enhance your skills, deepen your expertise, and lead with integrity. If you’re not currently affiliated with a subscribing organization, you can sign up as an independent learner. Check out the link in this episode’s description to learn more. And I just want to give a last special thanks to our line producer, Evelyn Fornell, and production and distribution support provided by Raymond Longaray and Megan Stuart. And with that, I look forward to bringing you all more conversations on all things tech ethics.

How to Listen and Subscribe to the Podcast

You can find On Tech Ethics with CITI Program available from several of the most popular podcast services. Subscribe on your favorite platform to receive updates when episodes are newly released. You can also subscribe to this podcast, by pasting “https://feeds.buzzsprout.com/2120643.rss” into your your podcast apps.

Recent Episodes

-

- Season 1 – Episode 40: Telehealth for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention

- Season 1 – Episode 39: Voice as a Biomarker of Diseases

- Season 1 – Episode 38: Active Physical Intelligence Explained

- Season 1 – Episode 37: Understanding the CMS Proposed Rule for Hospital Outpatient and Ambulatory Surgical Centers

Meet the Guests

Christina Kuhn, Esq – Covington & Burling LLP

Christina Kuhn advises medical device, life sciences, and technology companies on FDA regulation of AI, software, and digital health products. She helps companies navigate the FDA medical device framework to develop go-to-market strategies for innovative and emerging health technologies and manage compliance across the product lifecycle.

Olivia Dworkin, Esq – Covington & Burling LLP

Olivia Dworkin advises medical device, digital health, and technology companies on FDA regulatory and compliance matters across the product lifecycle. Her work centers on emerging medical technologies, including clinical decision support software, general wellness products, and AI-enabled health tools, helping companies manage risk while bringing innovative products to market.

Meet the Host

Daniel Smith, Director of Content and Education and Host of On Tech Ethics Podcast – CITI Program

As Director of Content and Education at CITI Program, Daniel focuses on developing educational content in areas such as the responsible use of technologies, humane care and use of animals, and environmental health and safety. He received a BA in journalism and technical communication from Colorado State University.