Season 3 – Episode 12 – Smart Tech, Smarter Questions: AI in Biomedical Research

In this episode, we examine how AI is transforming biomedical research and medical education, exposing deep flaws in legacy systems while offering a chance to rethink how knowledge is created, taught, and governed.

Podcast Chapters

Click to expand/collapse

To easily navigate through our podcast, simply click on the ☰ icon on the player. This will take you straight to the chapter timestamps, allowing you to jump to specific segments and enjoy the parts you’re most interested in.

- AI’s Inevitable Role in Science (00:00:01) AI’s adoption in research is unavoidable; the real question is how to make its impact positive.

- Podcast Introduction & Episode Overview (00:00:43) Host introduces the episode’s focus: AI’s transformation of biomedical research, education, and knowledge creation.

- Guest Introductions (00:02:10) Guests introduce themselves and their backgrounds in AI, medicine, and research.

- AI’s Impact on Research & Education (00:02:55) Discussion on how AI is transforming research methods, evaluation, and the inadequacy of traditional biostatistics.

- Risks of AI-Generated Science (00:04:48) Concerns about outsourcing knowledge creation to AI and the threat to human agency in scientific work.

- Overhauling Medical Knowledge Systems (00:07:39) AI’s potential to democratize medical knowledge and the need to rethink global knowledge systems.

- Where’s the Harm? AI as Tool and Risk (00:09:18) Exploring AI’s dual role as a tool and a risk, especially regarding scientific validity and ground truth.

- AI, Cheating, and Medical Education (00:11:44) How AI may facilitate shortcuts in learning, paralleling past concerns about plagiarism and internet use.

- External Incentives and Publish-or-Perish (00:13:47) Discussion of perverse incentives in research and education, and how AI may exacerbate these issues.

- AI as Fire: Opportunity and Threat (00:16:32) AI compared to fire—capable of destruction or creation—depending on how legacy systems are reformed.

- Rethinking Education: Teaching Thinking, Not Facts (00:16:51) AI’s impact on education, shifting focus from rote learning to teaching critical thinking skills.

- Challenges of Integrating AI in Medical Education (00:17:35) Difficulties in updating curricula and ensuring all students and professionals are AI-literate.

- On Campus Promo (00:19:22)

- Why Traditional Approaches Fall Short (00:19:48) Traditional research and education methods are insufficient; AI exposes and amplifies existing systemic flaws.

- Critical Thinking Through Diverse Collaboration (00:23:47) Critical thinking emerges from interdisciplinary, diverse groups rather than traditional, homogenous classrooms.

- Core Competencies Over Cutting-Edge Features (00:26:06) Emphasis on foundational skills (e.g., understanding bias, Bayesian thinking) over trendy technical knowledge.

- Designing Human-AI Systems for Virtue (00:27:18) Proposing human-AI systems that foster humility, curiosity, empathy, and connectedness.

- The Pace of AI and Outdated Curricula (00:28:55) AI’s rapid evolution outpaces traditional education and publication models, demanding new approaches.

- Who Should Shape the Future? (00:31:29) Young people and marginalized voices should lead the redesign of science and education.

- Science, Politics, and Advocacy (00:32:03) Science is inherently political; researchers must advocate for patients, not just institutional metrics.

- Ensuring Transparency and Integrity in AI Research (00:33:12) Journals and institutions must set clear standards for transparency, bias mitigation, and ethical AI use.

- Practical AI Literacy for All (00:36:21) Everyone in medicine should understand AI’s strengths, limitations, and how to use it responsibly.

- Future-Proofing Research Behavior, Not Just Metrics (00:38:00) Scientific publishing should document human involvement and deliberation, not just statistical results.

- Learning from History: Redesigning for the AI Era (00:39:54) Society must learn from past technological revolutions and intentionally design AI’s role in science.

- Episode Conclusion & Credits (00:41:07) Host thanks guests, summarizes key points, and provides information about further resources and credits.

Episode Transcript

Click to expand/collapse

Dr. Leo Anthony Celi: During a talk, I was asked, “Is AI worth its cost?” And I said, “That is the wrong question because if the answer is no, it doesn’t matter. The ship has sailed.” So the question should be, how can we make AI worth its cost? And it seems that the answer is simple. After a decade of doing research in this field, I must say that the answer we had reached is that the only way for us to make AI worth its cost is to fix the world.

Alexa McClellan: Welcome to On Research, the podcast where we explore the ideas, innovations, and ethical questions shaping higher education and research. I’m your host, Alexa McClellan. And today we’re exploring how artificial intelligence is transforming biomedical research and medical education. AI is evolving at a breakneck pace, changing not just what we can do in science, but how we do it, how we train students, how we structure research, and how we decide what counts as knowledge. But while the tools are changing quickly, the systems around them often lag behind. In this episode, we’ll talk about why current approaches to education and research are no longer enough, where the real risks and harms lie, and why this moment demands not just new tools, but new ways of thinking about science, learning, and human responsibility.

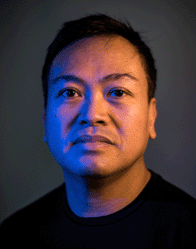

Joining me is Dr. Catherine Bielick, infectious diseases physician scientist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and clinical instructor at Harvard Medical School, and Dr. Leo Anthony Celi, clinical research director and senior research scientist at the MIT Laboratory Computational Physiology. Thank you both for being here.

Dr. Catherine Bielick: Thank you for having us.

Alexa McClellan: So to start with, can you introduce yourselves and talk about your background and expertise related to AI and biomedical research and medical education?

Dr. Leo Anthony Celi: My name is Leo Anthony Celi. I am a doctor. I work in the intensive care unit of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. And my research is based at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The focus is on the application of data science and artificial intelligence in healthcare delivery.

Alexa McClellan: Great. Thank you for being here. Catherine?

Dr. Catherine Bielick: Yeah. So my name’s Catherine Bielick. I’m an infectious disease physician at Beth Israel. I study artificial intelligence under grant funding to improve outcomes for people with HIV. So I do a lot of computational epidemiology and prediction of outcomes with medical records. And then the second half of my work is to discuss how bias can come to harm populations that are at the most vulnerable, especially if they’re not proactively mitigated or governed.

Alexa McClellan: Yeah, great. Thank you so much. So I want to spend some time today educating our listeners on how AI is transforming the landscape of medical education and biomedical research. So can you speak to that and share some examples? Let’s start with you, Catherine.

Dr. Catherine Bielick: Yes. So right now research is changing. I don’t even know that changing is the right word. It’s transforming right now in terms both of how it’s being conducted and also in terms of how it’s being evaluated and peer reviewed as well. Right now, the basic biostatistics that we’ve always relied on for education in order to evaluate some research papers are proving to be inadequate for evaluating very nuanced and sophisticated artificial intelligence discussions. And so from the ground up right now, the biomedical field of research is undergoing a total transformation.

We have people that are writing manuscripts with the use of AI or they’re assembling data with the use of AI. They’re implementing models without any evaluation frameworks and then reporting the results without a standardized reporting process. They’re going to report whatever metrics they feel like reporting. If they report global accuracy, they might not show that there was an imbalanced sample, whether that was because of ignorance, lack of training or something else.

These are very important features of AI research that not everyone knows to look for. If someone sees a 100% accuracy for something and they don’t know to look for data leakage. And this, from the ground up, is going to transform how we report science, how we read science and how we move forward with clinical care because we base all of our clinical care on science. And if it’s flawed, then it’s going to lead to a big problem down the road. As far as education goes, I mean, I think the education has to target that whole transformation from the bottom-up. And I’m sure there’s a lot more we could go into when it comes to that, but I’ll pause there.

Alexa McClellan: Yeah, thank you.

Dr. Leo Anthony Celi: So AI is promising us knowledge without the learning, and that could be very dangerous slope. With regard to biomedical research, I think we are a few months or maybe one to two years away from what we refer to as vibe science, where we could completely outsource the creation and validation of knowledge to AI. And at that point, we wouldn’t know what is the contribution of the humans in the lifecycle of that project. When I say vibe science, what I’m referring to is that we could dump a whole dataset. We could dump all the data that we collected into AI and ask it to write a manuscript, complete with an introduction, a methods, a result, and a discussion section, in which case, what would be our contribution? So I think that we need to rethink how we even write a scientific paper, because if 99.9% of the scientific paper is manufactured by AI, then again, human agency is at risk. Human agency is being threatened.

So I think the legacy of AI is making us reimagine what scientific inquiry might look like, what scientific dissemination might look like, and what medical education might look like. Because if the homework can be answered by AI, then it is a bad homework. And I could tell you that most of the tests and most of the assignments that we get during medical school can be answered by AI. So the challenge is, can we come up with questions, can we come up with evaluation framework that cannot be cheated, that cannot be answered by AI? And that is not straightforward. This, I think, is the biggest obstacle that we’re seeing as regards being able to leverage the power of this technology.

People are saying that you cannot use AI in medical education, you cannot use AI in biomedical research, and we actually think that that’s the wrong approach. We need to start teaching our learners, our students, to be able to use this smartly so that we could expand even further our universe. So we have a huge task ahead of us. As Catherine mentioned, there is an immense opportunity to overhaul the medical knowledge system, which we know has a lot of flaws. Our medical knowledge system is based on biomedical research that is performed by a small group of people coming from the global minority, and this medical knowledge is informing the way we practice medicine around the world.

AI, I think, is making us realize that there is an alternative to that. Everywhere data is being collected, everywhere data can be analyzed to create a local medical knowledge system, but that requires a different mindset, that requires different mode of thinking, that requires a different infrastructure. I think we are both very excited and very concerned with the onslaught of AI and the fact that AI now is in the air that we breathe. But if we not take advantage of this technology, I think it is because we fail to reimagine what the world might look like. We fail to reimagine how we educate, how we create knowledge, how we innovate. And to us, that would be a great, what do you call this? Loss to humanity.

Alexa McClellan: So I think just a general question I have is where’s the harm? So if AI is to the place where it can take and assimilate knowledge and write a research paper, is that hurting research as a whole? I think you talked about it limiting the content of what students are learning, and that makes sense, but is it a tool as well?

Dr. Catherine Bielick: It’s certainly a tool. It’s always hard to find a line when it comes to transforming technologies like this. I often think about what was the last technology that was so revolutionary for this on the bottom-up? And I think it would just have to be the internet and that completely changed the research process. You can now Google to find papers. You don’t need to know the Dewey decimal system in the library anymore. You can find papers at a moment’s notice. And how did we assimilate into the internet sphere? Very slowly. I think it took a long time for even Google Scholar to come out, even for librarians to trust it. But at the end of the day, people are still using it and it’s a good tool to help bring information and help people be more knowledgeable about things they wouldn’t have been as knowledgeable with otherwise.

And I think AI can do the same thing. It can educate us, it can tutor us, it can train us. The important thing to be aware of, and this will lead into how can it harm, is that large language models as a specific type of AI, they don’t have a real ground truth. And I think what’s important to take away from that is they don’t have a scientific method, and maybe that will change in the coming five years or two years. But as of now, it’s a limited context window. We’re still churning through tokens answering a zero shot or one shot prompt from a user, and your quality of output is still, we don’t do as much prompt engineering anymore, but it’s still governed by how well-formed your prompt was, how many contingencies you thought about, how many errors you tried to predict and tell it not to do.

And so if you’re looking at, well, who is doing the science and who should be doing the science? If an LLM is doing the science, then it’s just not real science. We’ll assemble knowledge into this big hotpot or I’m trying to think of a, cornucopia, I guess, of ideas that might mean something at the end of the day if it didn’t hallucinate something or it might be completely invalid. And if you’re not the one driving that, then you’ll never know.

Alexa McClellan: Yeah, that makes sense. What about in medical education? Can you speak to the harm that exists when students are using these AI tools to respond to homework? What are they not learning in that process?

Dr. Catherine Bielick: I’ve had discussions with some people about this too. I don’t want to beat a dead horse, but I think it’s the same idea as when people were worried about plagiarism because the internet allowed people to share each other’s work more easily. We currently have that. We’ll have take home assignments and people will go on, I have to think back to college and med school, but Quizlet and all these flashcard systems and people are sharing Anki flashcard decks with each other. No one’s synthesizing the information right now for board review.

That’s already happening. Is it a good thing just because it’s already happening? No, but it is and it hasn’t been an apocalypse right now of ignorance, necessarily. And I think it’s the same idea here. Can you micromanage a student from not plagiarizing an essay? At the end of the day, probably not. I think at the end of the day, they’re always going to find a way to brute force. If they want to cheat, they’re going to cheat. And I don’t know that you can stop someone from doing that. You can take as many protections as you want, but yeah, what’s the harm in someone taking that to the nth degree, well, it’s the harm of loss of education.

So if cheating becomes easier over time, I’m using the word cheating loosely, but if taking shortcuts becomes easier over time, then yeah, there’s going to be more people, I think, who take the shortcuts just because the activation energy to take those shortcuts is much lower. And so I think just the lower quality or fewer quantity of high quality physicians, as an example in medical education, would suffer at the end of the day. The second half of that, though, is that I think that there are an equal number, or perhaps more, people that aren’t driven and they want to use AI to improve themselves even more. So it’s not zero-sum, I think is the answer. So some people are going to take the shortcuts, and I think some people are going to figure out a way to make AI work for them to become something incredible as well.

Dr. Leo Anthony Celi: So paraphrasing that, AI is going to make smart people smarter and dumb people dumber, and it all boils down to what external reward systems do we have? I was having a debate with a colleague who is blaming the lack of fortitude of the young generation as the reason why we are going to see a decay in the quality of clinicians in the future. And I pushed back. I said that these students are reacting appropriately to the external rewards that we set out. So in biomedical research, what am I talking about? I am talking about the publish or perish culture. It turns out that the very first paper that mentioned this problem was published in 1928, and decade after a decade, investigators have been frustrated with the publish or perish culture as a perverse incentive to get promoted. So somehow we have decoupled metrics of learning with curiosity and the joy of learning.

Students are no longer doing research because they enjoy discovering something new. They’re doing research so that they can make their CVs more attractive, so that they could get into the top colleges, so that they could get into medical school and get into the top programs for residency. And we pay the price and that price is going to get steeper because of AI, because AI can get us those rewards much faster without us actually learning more in the process. So the legacy of AI, as I said, is making it so crystal clear how broken the systems are.

During a talk, I was asked, “Is AI worth its cost?” And I said, “That is the wrong question because if the answer is no, it doesn’t matter. The ship has sailed.” So the question should be, how can we make AI worth its cost? And it seems that the answer is simple. After a decade of doing research in this field, I must say that the answer we had reached is that the only way for us to make AI worth its cost is to fix the world. It’s to revamp legacy systems for education, for innovation, for knowledge creation. And if you don’t do this, AI is going to burn the world down because I was chuckling when Catherine was saying that what is an analogy for a technology as powerful as AI? And to me, it is fire. We are in a Promethean stage where we can either burn the world down with AI or we could create something beautiful.

Alexa McClellan: When I was preparing for this interview, I was reading about the way that we educate and how that has to change. In the past, we have educated by having students learn facts and then demonstrate their knowledge of those facts. And perhaps we should look at AI as changing that so that now we have to teach students how to think, not necessarily teach them the facts that they are supposed to reproduce, similar to how we use the calculator. We used to have to know to calculate those basic sums quickly and accurately. And now we use a calculator to do that, but yet we still use that as a springboard to move forward into higher level thinking. So perhaps we should take a similar approach with AI.

Dr. Catherine Bielick: Yeah, it would be complex to come up with an answer for that and how to restructure and target education. I think right now it feels more like damage control and making sure that people have the basic necessities at this point. It’s not going to be a single answer of, how can I educate the medical community about AI or how can we all educate each other about AI? Because everyone comes from such a chasm of difference in terms of what they know about what’s out there. I think we’ve missed the boat already. There are maybe some people that have immersed themselves in it, some that are following headlines or whatever. I think that there is a vast quantity of physicians already and students already that just, maybe they’ve never heard of ChatGPT or pick your favorite LLM and they’ve never logged into the website and it’s just not a part of their day-to-day anymore.

And for that, I think that we have already started to fail the medical community in that we haven’t brought that core competency to the people, I think, that need it the most. And I think that’s the people who know about it the least. One might argue that the people who need it the most are the ones that are going to be harmed by it. The most as well are at higher risk of harm. I think that would be a separate subject, but I agree with the idea. We’ll probably get up talking about that as well.

But yeah, as far as how to redesign medical education, it’s the same as we have courses for basic computer skills, but we don’t have that in medical school because we assume that you’re already a little fluent in it. We have board exams on computers now. And so if someone came in and they knew nothing about a computer, then they would not be able to take the board exam at that point. It’s integrated into everything that we already do at this point. And so I think in addition to directed education and damage control, then it just needs to be better integrated as well.

Ed Butch: I hope you are enjoying this episode of On Research. If you’re interested in important and diverse topics, the latest trends in the ever-changing landscape of universities, join me, Ed Butch, for CITI Program’s podcast On Campus. New episodes released monthly. Now back to On Research.

Alexa McClellan: It sounds like AI is really changing the way that research is conducted and the way that doctors are educated and how medicine is practiced. So why are traditional approaches to research and medical education no longer sufficient and what might a more holistic cross-disciplinary response to AI and biomedicine look like?

Dr. Leo Anthony Celi: It has never been sufficient. The problems that we face now are the same problems over the last century. We see the same health disparities. We see a medical knowledge system that is not representative of health and disease as experienced by people from around the world. And that is what excites me about AI. It’s giving us this immense opportunity to change all that, but it is not going to be straightforward. And I think the reason for that is that these institutions are very monolithic. They are so ossified, and AI requires agility. AI requires reflexivity and reflection, which we do not do in a regular fashion as doctors.

So we keep complaining about all the tasks that we do in our day-to-day lives leading to burnout. But if we stop for a moment and ask ourselves what of the tasks that we do are actually contributing to better patient outcomes, most doctors would say that, one, we don’t know. We haven’t really paused to think of how can we start from a clean slate and choose what should we be doing and how should we be doing those tasks? Say, for example, physical examination. That was introduced by Osler more than 100 years ago, and no one bothered to question what is the sensitivity and specificity of those things that I do as part of the physical examination?

Especially with technology now, we have to rethink the patient encounter. I, myself, think that we should spend most of the time just chatting with the patient and listening to them because those things that we perform, yes, they could take only five minutes or 10 minutes if you do it properly, but those add up very, very quickly. If you do that on all your patients, that’s a chunk of your time. And now people complain that the doctors spend too much time in front of the computer. I think it’s because we’re trying to keep up. We’re in front of the computer because now we have to worry about patient safety and quality improvement. Those were not in the minds of Osler. Those were not in the minds of doctors from 50 years ago, but we know that those are also important. So I think that it’s time to start with a clean slate.

It’s time to really identify what are we doing that is contributing to better population health. I remember I was in a conference, an international conference of ICU clinicians, and I asked the room, “How many of you know what proportion of your patients that you dialyze in the intensive care unit are alive in six months?” And the answer is around 50% and no one raised their hand. I asked them, “Is that information, do you think, important to us?” And everyone nodded, and I asked them, “So why don’t you know this number?” And I hear some excuses that data is not so easy to retrieve and I pushed back, “Of course, it is easy to retrieve, but there was no interest in getting that information.” So again, we have been hardwired to think in a certain way, and critical thinking is not one of them. I would push back to medical educators who insist that we teach critical thinking to our students.

We do not. Critical thinking is not telling them how to critically think. That is the complete opposite of critical thinking. And what we stumbled upon in the last decade or so is how to exercise critical thinking, and it’s actually not that difficult. Critical thinking magically happens when you bring people who don’t think alive together and you create a space where they could challenge each other, they can question each other. To a certain degree, it’s easier. So in the last decade, what our group has been doing is what we refer to bridge communities. So we travel around the world, we create communities, data communities of practice where we bring in people with different backgrounds across generations from high school all the way to professors of medicine, CEO of companies, and we put them in a small table, we give them topics, we give them algorithms that they set, we challenge them to think about unintended consequences of a particular algorithm, and we’ve challenged them even further, what guardrails can we erect so that we don’t see unintended consequences of these algorithm?

And the result is magic. You see solutions being conjured in front of your eyes, very creative solution. Some may sound crazy, but when you listen again, those crazy ideas are worth exploring. So we keep saying that you cannot teach critical thinking to a classroom of medical students. It’s not going to work because they think a lot. In order to teach critical thinking, you need to bring in students from computer science, from engineering, from anthropology, from linguistics, and suddenly guaranteed, you will see critical thinking conjured before your eyes.

Dr. Catherine Bielick: I completely agree. It’s too narrow, I think, to say that we just need to learn more about X cutting edge feature. Oh my gosh, my students don’t know what a model context protocol. It’s absurd to think about it like that, but at the same time, we look back and we see the same core issues that ever were. If I could be happy with people understanding the difference between a P-value and effect size, I would be a lot happier. If I could get people to acknowledge what Bayesian thinking is, which is just pre and post probabilities. You do a test and it changes probabilities instead of thinking in terms of black and white. I mean, I would be happy if we targeted anchoring bias better, we could hold better two conflicting ideas in our head at the same time. The assumption that old ways of doing things is the best way and the burden of proof is on the new way of doing things is also very challenging. Having humility is not something that can really be taught, but if it were focused on more, then I think we’d come a long way.

Alexa McClellan: Well, how can we use AI tools and integrate them with the curriculum to enhance critical thinking in our medical students?

Dr. Leo Anthony Celi: We have been thinking about how do we design human AI systems that enhance human virtues. Now in our discussions, we actively say, “Perhaps we should stop building models because we are drowning in models.” What we need to do is to design human AI systems that will allow us to have more critical thinking. And what does that entail? Perhaps we could have AI to nudge us to consult other people who don’t think like us. Perhaps AI can be used as a tool to improve our connectiveness because decades of research in happiness have told us that the key to happiness is one, good health and second, connection. And perhaps this can be part of the design of human AI systems. Going back to Catherine’s point of humility, how do we design human AI systems that will make humans more humble, more curious, more empathetic?

We need AI that will put us on the rails. We need humans that will put AI on the rails. With each component, the humans and AI being aware of each other’s limitations and opportunities. But that sounds very different from what we are doing now, which is just let’s look for a dataset, let’s find something to predict and then see what model sticks when it comes to some statistical model performance. We keep saying that if all you’re doing is dumping gobs and gobs of data and seeing what sticks with respect to accuracy, then we are doomed to permanently cement disparities in care, structural inequalities. So we have to think about how do we teach AI to our students. It’s not going to be our typical course.

For one, it is a field that is moving so fast. The classrooms of today are in Zoom meetings, Teams meetings, they’re in WhatsApp, they’re in Signal, they’re in social media. That’s how we are learning about discoveries in AI. This is why classrooms are going to fail because by the time you have a curriculum, it is already outdated. This is why journals are going to fail. By the time you finish a prospective randomized control trial evaluating an AI, that AI is already outdated. It is no longer going to perform similarly compared to the time when it was trained. So how do we rethink scientific dissemination if it takes too much time to publish a study? How do we think education when a field is moving at a pace we have never seen before? We have to be more creative, we have to be smarter, we have to be more deliberate of what do we want to teach. And what we love about AI is it’s truly providing us with a forcing function of asking ourselves, what is it that we want?

I never set out to be a philosopher or to be an activist or advocate, but it became clear that we needed to be one in order to fully leverage this technology. So when we say progress, what exactly do we mean? Whose progress and what is the benefit of that progress to everyone? When we say efficiency, whose time is saved as a result of efficiency? In this world where there is corporatization of healthcare, being efficient might mean being given more patients to see, in which case we are just rearranging the furniture of a sinking Titanic. So again, the challenge, and this is what excites me, is for us to completely rethink what are we doing on a day-to-day basis.

Alexa McClellan: Leo, who should be involved in that conversation? When you say we, who are the players that should be at the table to make those choices?

Dr. Leo Anthony Celi: The players are the young people because the young people are not as cynical as old farts like me. They are crazier when it comes to their ideas. I love the saying, “We need to brainstorm like a child, but implement like an adult.” And of course, do not forget those whose voices have been traditionally muted in the creation of knowledge and the discovery of science. And I also wanted to say that people say that science should be apolitical. Science can never be apolitical. Science is created and evaluated and leveraged in a non-neutral space. In the end, the impact of science or any innovation truly hinges on who gets to control science and the innovations. So I said earlier, I did not intend to be an activist. I did not intend to be an advocate, but to me, that is the most important transformation is that every young doctor, young nurse, young pharmacist, they have to be true advocates of the patients and not advocates of the key performance indicators, the bottom line, because we have become slaves to those numbers.

Alexa McClellan: We bring up that science is apolitical, but I do wonder what responsibilities journalists, institutions, and researchers have in ensuring transparency and integrity with these AI tools. Catherine, can you speak to that? What responsibilities do journals and institutions and researchers have in ensuring transparency and integrity in AI-assisted research?

Dr. Catherine Bielick: I think the same expectations should be applied to individuals as to institutions and journals. And there should be some agreement. I think we should come together about what are the non-negotiables and core competencies that we want to die on the hill for. It is effectively where our ethics fall down to, because at some point we do have to say, no, you shouldn’t be publishing this model because it is deeply flawed. And if someone bought it off the shelf and implemented it, then it would hurt a lot of people. For example, I think I saw last year, not to call this journal out, but it was in one of the [inaudible 00:34:02] journals, I think. There was a study that built a model. It was a convolutional neural network looking at retinal scans. I’m not sure about the precedent for what went into the research question, but they were looking to help diagnose autism spectrum disorder using retinal scans.

So okay, you take a look at it and in the results it reports a 100% specificity, a 100% sensitivity all down the precision recall metrics, it had 100%. And I look at that and I’m just like, “This made it into a journal.” And I’ll bring it to some of my colleagues and say, “Do you see that there might be an issue here, first of all? And we don’t have to talk about what the issue is, but you see that there’s a red flag?” And some have been able to pick up and you look into the paper, you look into the supplemental methods and it’ll show the retinal scans for the training group for the non-neurodivergent kids. And then for the neurodivergent kids, it gives a sampling. And one of them is a pink retinal scan in a brightly lit room, and one is a darker one because the kids with autism spectrum disorder needed dimming of the lights.

And so this convolutional neural network didn’t really diagnose ASD, it diagnosed a dark room. And this is the concept of data leakage, and it’s not the only hill to die on, but I do think that journals and institutions need to know what that is, and it should be something that we can all agree on should be called out and should be proactively mitigated in some way. I’m not going to be able to prescribe and come up with the whole solution for that, but that’s one example. I think people, on a practical level, if institutions are putting LLMs into a hospital system or a clinic, for example, yeah, then the people on the ground need to know how to use it and they need to know what the limitations are. You can’t just roll out a tool, expect everybody to use it or give everyone the freedom to use it and not know what the even most fundamental limitations of a large language model are.

And so I think that is how we would wrap all of it up into one package and say, “Well, what would I teach in a medical education system?” And it’s the same expectations I think that I would have for institutions and journals. I need for people, we all need for people to know what it’s good for. It’s good for idea generation, it’s good for task automation, it’s good for document retrieval. It’s good at fact finding. It really is. I mean, a foundation model, if we’re going to go to Google search something, then it’s good to use AI. It is trained on a large amount of the internet. And if you’re effectively already searching through the internet for something, then yeah, it’s good, better than some of the tools that we’ve been using all this time. We should have basic education about what a good prompt is and how to iteratively improve your output.

I think these are very important things that, if you just start typing away on a language model, you wouldn’t know that you’re getting worse results due to something that could have been intervened on. And for limitations, I think we could talk all day about all the limitations, but we do need to come and agree that data leakage needs to be called out. We must know what the different types of bias are when it comes to models, algorithmic bias and sampling bias. We have to know what went into that so that the second piece of that, which is transparency of methods and the coding systems, we need to be able to know what to look for.

If we just have transparency and we don’t even know what to look for, then it doesn’t really gain us anything. We have to know how to recognize hallucinations. We have to know when a language model loses its attention on what you were talking about. You have to know what internal and external validity are. You can’t train a model on a rural area of Arizona and bring it over to upstate New York or Manhattan and expect it to perform the same. These are things that I would expect journals and institutions to care about, and I would give accountability to them. And these are also things that I would want to teach rising medical professionals.

Dr. Leo Anthony Celi: I’m just going to add that, in addition to what Catherine said, the journals have to rethink exactly what their role is because in the past what we have seen is sensationalizing of science, and we have been obsessed with the P-value. We have been obsessed with right now the AUC, the AUPRC, some statistical estimates of model performance. And with AI, that’s different. Well, you can argue that with everything else, it’s the same way, that the P-value that’s being reported is tied to the conditions of the trials. It’s tied to the condition when the data was collected. So rather than future-proofing the P-value, rather than future-proofing the model performance, what we need to future-proof is the research behavior. And this is why we think that the scientific paper of tomorrow should not be introduction, methods, results, and discussion. It should be evidence that humans were involved at every step of the way.

So we would like to hear why was that question tackled? What was the deliberation that ensued? How was that question translated into a study design? What were the assumptions that were made and how did the investigators check those assumptions? What would that look like? We don’t know. We actually have an upcoming special collection soliciting prototypes and archetypes of what this might look like. It could be snippets of conference calls, but again, this is going to look radically different from what we have now. So we are in a very thrilling part of society, but we have to learn from history. I love the saying that one thing we could learn from history is we never learned from history. So when the printing press was introduced, when electricity was introduced, it took decades before we were able to see the value of the printing press and electricity.

And we need to understand the hiccups that we’re seeing, that we’re stumbled upon as a result of a very powerful innovation that was introduced. But again, this would require bringing people who think differently to redesign the world. This would require not a meeting of the minds, but a meaning of the souls, a meeting of the hearts to freely figure out where do we want to go to. So this is a call to institutions of education, institutions of innovation, to start reflecting what is it that we want and how do we design so that we could optimize the use of this technology.

Alexa McClellan: Leo and Catherine, thank you so much for your time. It has been a joy talking with you. I think you gave us a lot to think about.

Dr. Catherine Bielick: Thank you so much for having us. It was a real pleasure.

Dr. Leo Anthony Celi: Thank you.

Alexa McClellan: And that’s it for today’s episode of On Research, a huge thank you to Dr. Catherine Bielick and Dr. Leo Celi for helping us navigate such a complex and timely topic. As AI becomes more deeply embedded in science and medicine, we have a choice. We can react slowly and let the technology define us, or we can respond boldly and thoughtfully, bringing together educators, researchers, students, and innovators to shape the future we actually want to live in. CITI Program offers self-paced courses in research compliance, including on animal and human subjects research, responsible conduct of research, and research security. Enhance your skills, deepen your expertise, and lead with integrity across research settings. If you’re not currently affiliated with a subscribing organization, you can sign up as an independent learner and access CITI Program’s full course catalog. Check out the link in this episode’s description to learn more.

As a reminder, I want to quickly note that this podcast is for educational purposes only. It is not designed to provide legal advice or legal guidance. You should consult with your organization’s attorneys if you have questions or concerns about the relevant laws and regulations that may be discussed in this podcast. In addition, the views expressed in this podcast are solely those of our guests. Cynthia Bellis is our guest experience producer, and Evelyn Fornell is our line producer. Production and distribution support provided by Raymond Longaray and Megan Stuart. Thanks for listening.

How to Listen and Subscribe to the Podcast

You can find On Research with CITI Program available from several of the most popular podcast services. Subscribe on your favorite platform to receive updates when episodes are newly released. You can also subscribe to this podcast, by pasting “https://feeds.buzzsprout.com/2112707.rss” into your your podcast apps.

Recent Episodes

-

- Season 3 – Episode 11: 2025 PRIM&R Annual Conference Roundup

- Season 3 – Episode 10: Ethics, Innovation, and the Future of Animal Research

- Season 3 – Episode 9: Black Women in Clinical Research: Building Community and Breaking Barriers

- Season 3 – Episode 8: The NIH Mandate for Posting IBC Minutes: Guidance for Institutions

Meet the Guests

Catherine Bielick, MD, MS, MS – Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center

Catherine Bielick is an Infectious Diseases Physician Scientist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Clinical Instructor at Harvard Medical School. She studies use of artificial intelligence to improve outcomes for people with HIV. She also studies ethics, bias, regulation science, and improving medical education related to healthcare AI.

Leo Anthony Celi, MD, MS, MPH – Massachusetts Institute of Technology; Harvard Medical School

Dr. Celi is the principal investigator behind the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care and its offspring, MIMIC-CXR, MIMIC-ED, MIMIC-ECHO, and MIMIC-ECG. With close to 100k users worldwide, an open codebase, and close to 10k publications in Google Scholar, the datasets have shaped the course of machine learning in healthcare.

Meet the Host

Alexa McClellan, MA, Host, On Research Podcast – CITI Program

Alexa McClellan is the host of CITI Program’s On Research Podcast. She is the Associate Director of Research Foundations at CITI Program. Alexa focuses on developing content related to academic and clinical research compliance, including human subjects research, animal care and use, responsible conduct of research, and conflict of interests. She has over 17 years of experience working in research administration in higher education.